History

History

The Sinai War/Suez Crisis - 1956

The Sinai War/Suez Crisis - 1956

Nov 29, 2025

Watch on Youtube

The Suez Crisis – PragerU (Michael Oren)

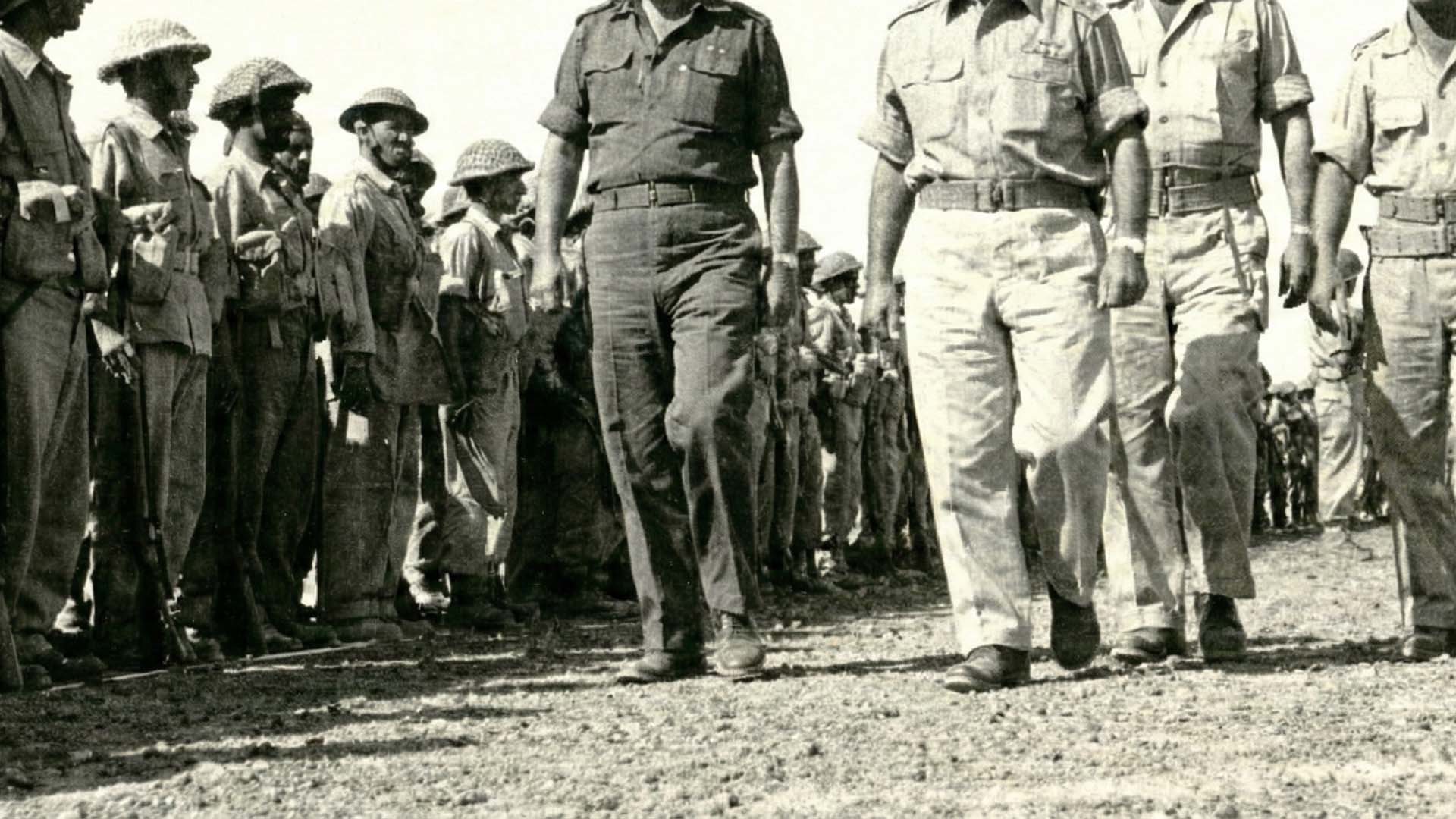

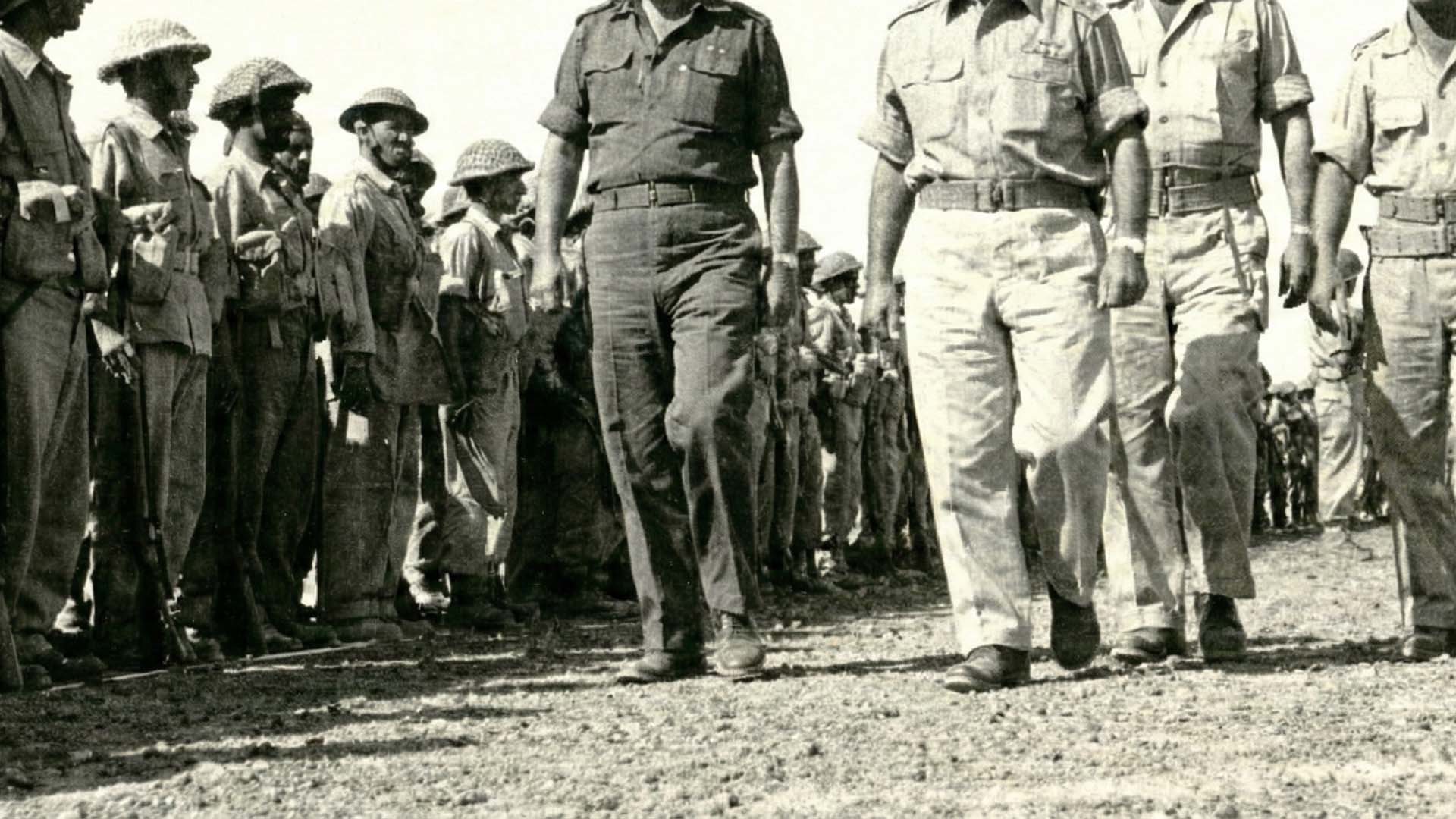

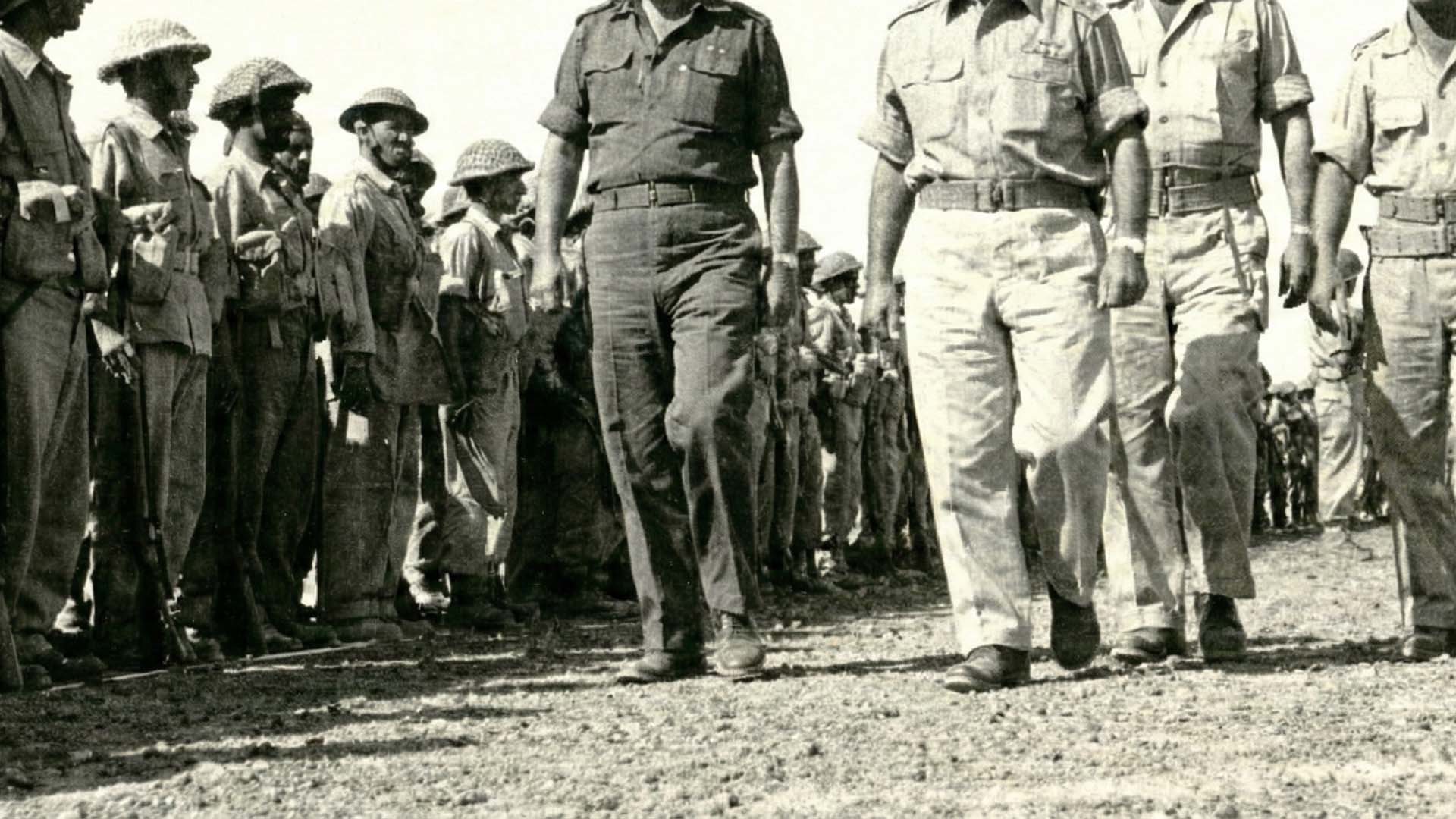

Just before dawn on October 29, 1956, paratroopers of the Israel Defense Forces, led by the legendary commander Ariel Sharon, descended into Egypt’s Sinai Desert.

Their goal was to conquer the strategically important Mitla Pass — but the broader objective was to eliminate the threat posed by the Soviet-armed Egyptian military and Egypt’s strongman, Gamal Abdel Nasser.

Israel was not alone in seeking Nasser’s defeat. Great Britain and France also wanted to intervene against him, after he nationalized the economically vital Suez Canal.

They only needed a pretext — and Israel provided one by attacking Egyptian forces near the Mitla Pass, about 20 miles from the canal.

Thus began what is known as the Suez Crisis, or the Second Arab–Israeli War.

Origins of the War

The war’s origins can be traced to the end of Israel’s War of Independence in 1949, when Israel signed armistice agreements with Jordan, Egypt, and Syria.

Israel viewed these agreements as a first step toward peace — but the Arab states saw them only as temporary truces, leading up to what they called “the second round” to destroy Israel.

Throughout the early 1950s, the Arab states acquired modern weapons — especially fighter jets — which Israel, still under a U.S. arms embargo, could not obtain.

The Arab states also supported Palestinian terrorist bands known as fedayeen (“self-sacrificers”), who launched raids against Israeli communities from the West Bank (then ruled by Jordan) and from the Gaza Strip (ruled by Egypt).

In response, Israel formed elite paratrooper units under Ariel Sharon to retaliate against the fedayeen raids. Border tensions escalated rapidly — yet war still seemed unlikely unless a unifying Arab leader emerged.

That leader was the charismatic Gamal Abdel Nasser, who electrified Arabic-speaking audiences with fiery rhetoric against the West.

Nasser’s Rise and Soviet Support

After seizing power in July 1952, Nasser portrayed himself as the hero of Pan-Arabism — the idea that all Arab nations should unite into one powerful state.

He railed against “the Zionist entity,” refusing to call Israel by name, and pledged to fight it.

He rejected repeated American and British peace proposals, even when they offered him large areas of Israel’s Negev desert in return.

Instead, he intensified the fedayeen attacks and sought advanced weaponry from the West’s main rival — the Soviet Union.

In September 1955, he succeeded, signing a massive arms deal with Moscow that included hundreds of tanks, armored vehicles, and modern fighter jets and bombers.

Suddenly outgunned by Egypt and surrounded by hostile states, Israel’s very existence seemed in jeopardy — or so believed Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion and IDF Chief of Staff Moshe Dayan.

Alliance with France and Britain

Israel desperately needed an ally — and found one in France.

When Nasser began supporting Algeria’s war of independence against French rule, France and Israel discovered a common enemy.

Secretly at first, France began supplying Israel with weapons — but for Ben-Gurion and Dayan, it wasn’t fast enough. They feared Egypt would soon be ready to strike.

The opportunity to preempt that attack came in July 1956, when Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal.

Britain and France, who largely owned the canal, were ready to retake it by force — but needed a pretext.

In a secret agreement, Israel committed to land paratroopers in the Mitla Pass near the canal.

This would trigger a chain of planned events:

Britain and France would issue an ultimatum to both Egypt and Israel to stop “threatening” the waterway.

Both were expected to reject the demand — giving Britain and France the excuse to launch a joint invasion “to protect” the canal.

It was a bold — even reckless — scheme, certain to anger U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower, who publicly opposed the use of force against Nasser.

That’s why the plan remained secret until October 29, 1956, when the Israeli paratroopers landed in Mitla.

The War and Its Outcome

Simultaneously, Israeli ground forces smashed through Egyptian lines in the Sinai, while Israel’s French-made jets shot down Egypt’s Soviet-made MiGs.

Within 100 hours, all of Sinai — down to the Suez Canal — and all of Gaza were in Israeli hands.

Britain and France issued their ultimatum — but then failed to act.

Eisenhower, feeling betrayed, was furious and warned of serious repercussions if they invaded.

Despite U.S. objections, they proceeded — but only after five days of delay, and their progress was painfully slow.

That gave the U.S. and the United Nations time to condemn the invasion and demand an immediate withdrawal.

The invading forces retreated in disgrace, and both the British and French governments fell soon after.

Israel, too, was pressured by the U.S. to withdraw its troops.

A first-ever UN peacekeeping force was deployed in Sinai and Gaza.

Still, Israel had eliminated the immediate Egyptian threat and secured a decade of relative quiet.

Ben-Gurion and Dayan became national heroes, and Israel could now focus on absorbing new immigrants, building its economy, and strengthening the IDF — in preparation for the far greater challenge that would come in 1967.

— Michael Oren, author of “Six Days of War,” for Prager University.

A former paratrooper and reserve commander takes us from the frontlines to the world stage — describing life in Sderot, fighting inside Gaza (Machon Al-Quds, Nuseirat, Beit Hanoun) and the trauma of October 7. He explains how close Gaza is to Israeli towns, recalls the 2005 Gush Katif withdrawal, and shares raw, personal scenes from months spent in active combat — then returning home to face a different battle: the rise of antisemitism worldwide. What you’ll hear in this video: • A frontline commander’s personal testimony about October 7 and the months that followed. • Firsthand descriptions of operations in Gaza (Nuseirat, Beit Hanoun) and daily threats from tunnels and armed militants. • Reflections on the 2005 Gaza withdrawal (Gush Katif) and what it meant for local communities. • The psychological shift from military duty back to civilian life and confronting global antisemitism.

Tommy Robinson visits Re’im, the site of the Nova Festival massacre, during the two-year memorial of the October 7th atrocities. Hear the harrowing first-hand testimonies of survivors and witnesses as they recount what truly happened when Hamas terrorists attacked innocent festivalgoers. This is the raw, unfiltered truth of that dark day, as told by those who lived through it.

After watching previously unseen footage showing the massacre of 110 innocent people by Hamas on October 7th, Tommy Robinson shares his raw reaction and reflections. He speaks about what he witnessed, the mindset behind the attacks, and how the reality on the ground in Israel differs from what much of the media shows. This is not easy to watch — but it’s an honest account of what he saw and why he believes the world needs to understand the true nature of this conflict.

Today I visited the Kibbutz closest to the Gaza border. Where some 5,000 Hamas jihadist scum launched their attack on Israeli citizens on October 7th. I speak to this brave gentleman, Thomas Hand, whose 8 year old daughter was kidnapped by the terror group that day. Listen to the harrowing testimony of a father, one story, amongst thousands. Thank you for sharing your experience Thomas. This video is not for the feint of heart.

In this explosive interview, Amichai Chikli Minister of Diaspora Affairs of Israel delivers a powerful warning about the rise of radical Islam and the Muslim Brotherhood’s dangerous global ambitions, from establishing a Caliphate to imposing Sharia law across Europe and beyond. He slams the UK’s Labour government under Keir Starmer for its "fear-driven" approach to extremism, drawing chilling parallels to appeasement tactics before WWII. Discover why he believes Britain must act decisively to avoid a catastrophic wake-up call. Join the conversation on this critical fight for freedom and democracy!

A former paratrooper and reserve commander takes us from the frontlines to the world stage — describing life in Sderot, fighting inside Gaza (Machon Al-Quds, Nuseirat, Beit Hanoun) and the trauma of October 7. He explains how close Gaza is to Israeli towns, recalls the 2005 Gush Katif withdrawal, and shares raw, personal scenes from months spent in active combat — then returning home to face a different battle: the rise of antisemitism worldwide. What you’ll hear in this video: • A frontline commander’s personal testimony about October 7 and the months that followed. • Firsthand descriptions of operations in Gaza (Nuseirat, Beit Hanoun) and daily threats from tunnels and armed militants. • Reflections on the 2005 Gaza withdrawal (Gush Katif) and what it meant for local communities. • The psychological shift from military duty back to civilian life and confronting global antisemitism.

Tommy Robinson visits Re’im, the site of the Nova Festival massacre, during the two-year memorial of the October 7th atrocities. Hear the harrowing first-hand testimonies of survivors and witnesses as they recount what truly happened when Hamas terrorists attacked innocent festivalgoers. This is the raw, unfiltered truth of that dark day, as told by those who lived through it.

After watching previously unseen footage showing the massacre of 110 innocent people by Hamas on October 7th, Tommy Robinson shares his raw reaction and reflections. He speaks about what he witnessed, the mindset behind the attacks, and how the reality on the ground in Israel differs from what much of the media shows. This is not easy to watch — but it’s an honest account of what he saw and why he believes the world needs to understand the true nature of this conflict.

Today I visited the Kibbutz closest to the Gaza border. Where some 5,000 Hamas jihadist scum launched their attack on Israeli citizens on October 7th. I speak to this brave gentleman, Thomas Hand, whose 8 year old daughter was kidnapped by the terror group that day. Listen to the harrowing testimony of a father, one story, amongst thousands. Thank you for sharing your experience Thomas. This video is not for the feint of heart.

In this explosive interview, Amichai Chikli Minister of Diaspora Affairs of Israel delivers a powerful warning about the rise of radical Islam and the Muslim Brotherhood’s dangerous global ambitions, from establishing a Caliphate to imposing Sharia law across Europe and beyond. He slams the UK’s Labour government under Keir Starmer for its "fear-driven" approach to extremism, drawing chilling parallels to appeasement tactics before WWII. Discover why he believes Britain must act decisively to avoid a catastrophic wake-up call. Join the conversation on this critical fight for freedom and democracy!

A former paratrooper and reserve commander takes us from the frontlines to the world stage — describing life in Sderot, fighting inside Gaza (Machon Al-Quds, Nuseirat, Beit Hanoun) and the trauma of October 7. He explains how close Gaza is to Israeli towns, recalls the 2005 Gush Katif withdrawal, and shares raw, personal scenes from months spent in active combat — then returning home to face a different battle: the rise of antisemitism worldwide. What you’ll hear in this video: • A frontline commander’s personal testimony about October 7 and the months that followed. • Firsthand descriptions of operations in Gaza (Nuseirat, Beit Hanoun) and daily threats from tunnels and armed militants. • Reflections on the 2005 Gaza withdrawal (Gush Katif) and what it meant for local communities. • The psychological shift from military duty back to civilian life and confronting global antisemitism.

Tommy Robinson visits Re’im, the site of the Nova Festival massacre, during the two-year memorial of the October 7th atrocities. Hear the harrowing first-hand testimonies of survivors and witnesses as they recount what truly happened when Hamas terrorists attacked innocent festivalgoers. This is the raw, unfiltered truth of that dark day, as told by those who lived through it.

After watching previously unseen footage showing the massacre of 110 innocent people by Hamas on October 7th, Tommy Robinson shares his raw reaction and reflections. He speaks about what he witnessed, the mindset behind the attacks, and how the reality on the ground in Israel differs from what much of the media shows. This is not easy to watch — but it’s an honest account of what he saw and why he believes the world needs to understand the true nature of this conflict.

Today I visited the Kibbutz closest to the Gaza border. Where some 5,000 Hamas jihadist scum launched their attack on Israeli citizens on October 7th. I speak to this brave gentleman, Thomas Hand, whose 8 year old daughter was kidnapped by the terror group that day. Listen to the harrowing testimony of a father, one story, amongst thousands. Thank you for sharing your experience Thomas. This video is not for the feint of heart.

In this explosive interview, Amichai Chikli Minister of Diaspora Affairs of Israel delivers a powerful warning about the rise of radical Islam and the Muslim Brotherhood’s dangerous global ambitions, from establishing a Caliphate to imposing Sharia law across Europe and beyond. He slams the UK’s Labour government under Keir Starmer for its "fear-driven" approach to extremism, drawing chilling parallels to appeasement tactics before WWII. Discover why he believes Britain must act decisively to avoid a catastrophic wake-up call. Join the conversation on this critical fight for freedom and democracy!

A former paratrooper and reserve commander takes us from the frontlines to the world stage — describing life in Sderot, fighting inside Gaza (Machon Al-Quds, Nuseirat, Beit Hanoun) and the trauma of October 7. He explains how close Gaza is to Israeli towns, recalls the 2005 Gush Katif withdrawal, and shares raw, personal scenes from months spent in active combat — then returning home to face a different battle: the rise of antisemitism worldwide. What you’ll hear in this video: • A frontline commander’s personal testimony about October 7 and the months that followed. • Firsthand descriptions of operations in Gaza (Nuseirat, Beit Hanoun) and daily threats from tunnels and armed militants. • Reflections on the 2005 Gaza withdrawal (Gush Katif) and what it meant for local communities. • The psychological shift from military duty back to civilian life and confronting global antisemitism.

Tommy Robinson visits Re’im, the site of the Nova Festival massacre, during the two-year memorial of the October 7th atrocities. Hear the harrowing first-hand testimonies of survivors and witnesses as they recount what truly happened when Hamas terrorists attacked innocent festivalgoers. This is the raw, unfiltered truth of that dark day, as told by those who lived through it.

After watching previously unseen footage showing the massacre of 110 innocent people by Hamas on October 7th, Tommy Robinson shares his raw reaction and reflections. He speaks about what he witnessed, the mindset behind the attacks, and how the reality on the ground in Israel differs from what much of the media shows. This is not easy to watch — but it’s an honest account of what he saw and why he believes the world needs to understand the true nature of this conflict.

Today I visited the Kibbutz closest to the Gaza border. Where some 5,000 Hamas jihadist scum launched their attack on Israeli citizens on October 7th. I speak to this brave gentleman, Thomas Hand, whose 8 year old daughter was kidnapped by the terror group that day. Listen to the harrowing testimony of a father, one story, amongst thousands. Thank you for sharing your experience Thomas. This video is not for the feint of heart.

In this explosive interview, Amichai Chikli Minister of Diaspora Affairs of Israel delivers a powerful warning about the rise of radical Islam and the Muslim Brotherhood’s dangerous global ambitions, from establishing a Caliphate to imposing Sharia law across Europe and beyond. He slams the UK’s Labour government under Keir Starmer for its "fear-driven" approach to extremism, drawing chilling parallels to appeasement tactics before WWII. Discover why he believes Britain must act decisively to avoid a catastrophic wake-up call. Join the conversation on this critical fight for freedom and democracy!

A former paratrooper and reserve commander takes us from the frontlines to the world stage — describing life in Sderot, fighting inside Gaza (Machon Al-Quds, Nuseirat, Beit Hanoun) and the trauma of October 7. He explains how close Gaza is to Israeli towns, recalls the 2005 Gush Katif withdrawal, and shares raw, personal scenes from months spent in active combat — then returning home to face a different battle: the rise of antisemitism worldwide. What you’ll hear in this video: • A frontline commander’s personal testimony about October 7 and the months that followed. • Firsthand descriptions of operations in Gaza (Nuseirat, Beit Hanoun) and daily threats from tunnels and armed militants. • Reflections on the 2005 Gaza withdrawal (Gush Katif) and what it meant for local communities. • The psychological shift from military duty back to civilian life and confronting global antisemitism.

Tommy Robinson visits Re’im, the site of the Nova Festival massacre, during the two-year memorial of the October 7th atrocities. Hear the harrowing first-hand testimonies of survivors and witnesses as they recount what truly happened when Hamas terrorists attacked innocent festivalgoers. This is the raw, unfiltered truth of that dark day, as told by those who lived through it.

After watching previously unseen footage showing the massacre of 110 innocent people by Hamas on October 7th, Tommy Robinson shares his raw reaction and reflections. He speaks about what he witnessed, the mindset behind the attacks, and how the reality on the ground in Israel differs from what much of the media shows. This is not easy to watch — but it’s an honest account of what he saw and why he believes the world needs to understand the true nature of this conflict.

Today I visited the Kibbutz closest to the Gaza border. Where some 5,000 Hamas jihadist scum launched their attack on Israeli citizens on October 7th. I speak to this brave gentleman, Thomas Hand, whose 8 year old daughter was kidnapped by the terror group that day. Listen to the harrowing testimony of a father, one story, amongst thousands. Thank you for sharing your experience Thomas. This video is not for the feint of heart.

In this explosive interview, Amichai Chikli Minister of Diaspora Affairs of Israel delivers a powerful warning about the rise of radical Islam and the Muslim Brotherhood’s dangerous global ambitions, from establishing a Caliphate to imposing Sharia law across Europe and beyond. He slams the UK’s Labour government under Keir Starmer for its "fear-driven" approach to extremism, drawing chilling parallels to appeasement tactics before WWII. Discover why he believes Britain must act decisively to avoid a catastrophic wake-up call. Join the conversation on this critical fight for freedom and democracy!

A former paratrooper and reserve commander takes us from the frontlines to the world stage — describing life in Sderot, fighting inside Gaza (Machon Al-Quds, Nuseirat, Beit Hanoun) and the trauma of October 7. He explains how close Gaza is to Israeli towns, recalls the 2005 Gush Katif withdrawal, and shares raw, personal scenes from months spent in active combat — then returning home to face a different battle: the rise of antisemitism worldwide. What you’ll hear in this video: • A frontline commander’s personal testimony about October 7 and the months that followed. • Firsthand descriptions of operations in Gaza (Nuseirat, Beit Hanoun) and daily threats from tunnels and armed militants. • Reflections on the 2005 Gaza withdrawal (Gush Katif) and what it meant for local communities. • The psychological shift from military duty back to civilian life and confronting global antisemitism.

Tommy Robinson visits Re’im, the site of the Nova Festival massacre, during the two-year memorial of the October 7th atrocities. Hear the harrowing first-hand testimonies of survivors and witnesses as they recount what truly happened when Hamas terrorists attacked innocent festivalgoers. This is the raw, unfiltered truth of that dark day, as told by those who lived through it.

After watching previously unseen footage showing the massacre of 110 innocent people by Hamas on October 7th, Tommy Robinson shares his raw reaction and reflections. He speaks about what he witnessed, the mindset behind the attacks, and how the reality on the ground in Israel differs from what much of the media shows. This is not easy to watch — but it’s an honest account of what he saw and why he believes the world needs to understand the true nature of this conflict.

Today I visited the Kibbutz closest to the Gaza border. Where some 5,000 Hamas jihadist scum launched their attack on Israeli citizens on October 7th. I speak to this brave gentleman, Thomas Hand, whose 8 year old daughter was kidnapped by the terror group that day. Listen to the harrowing testimony of a father, one story, amongst thousands. Thank you for sharing your experience Thomas. This video is not for the feint of heart.

In this explosive interview, Amichai Chikli Minister of Diaspora Affairs of Israel delivers a powerful warning about the rise of radical Islam and the Muslim Brotherhood’s dangerous global ambitions, from establishing a Caliphate to imposing Sharia law across Europe and beyond. He slams the UK’s Labour government under Keir Starmer for its "fear-driven" approach to extremism, drawing chilling parallels to appeasement tactics before WWII. Discover why he believes Britain must act decisively to avoid a catastrophic wake-up call. Join the conversation on this critical fight for freedom and democracy!

A former paratrooper and reserve commander takes us from the frontlines to the world stage — describing life in Sderot, fighting inside Gaza (Machon Al-Quds, Nuseirat, Beit Hanoun) and the trauma of October 7. He explains how close Gaza is to Israeli towns, recalls the 2005 Gush Katif withdrawal, and shares raw, personal scenes from months spent in active combat — then returning home to face a different battle: the rise of antisemitism worldwide. What you’ll hear in this video: • A frontline commander’s personal testimony about October 7 and the months that followed. • Firsthand descriptions of operations in Gaza (Nuseirat, Beit Hanoun) and daily threats from tunnels and armed militants. • Reflections on the 2005 Gaza withdrawal (Gush Katif) and what it meant for local communities. • The psychological shift from military duty back to civilian life and confronting global antisemitism.

Tommy Robinson visits Re’im, the site of the Nova Festival massacre, during the two-year memorial of the October 7th atrocities. Hear the harrowing first-hand testimonies of survivors and witnesses as they recount what truly happened when Hamas terrorists attacked innocent festivalgoers. This is the raw, unfiltered truth of that dark day, as told by those who lived through it.

After watching previously unseen footage showing the massacre of 110 innocent people by Hamas on October 7th, Tommy Robinson shares his raw reaction and reflections. He speaks about what he witnessed, the mindset behind the attacks, and how the reality on the ground in Israel differs from what much of the media shows. This is not easy to watch — but it’s an honest account of what he saw and why he believes the world needs to understand the true nature of this conflict.

Today I visited the Kibbutz closest to the Gaza border. Where some 5,000 Hamas jihadist scum launched their attack on Israeli citizens on October 7th. I speak to this brave gentleman, Thomas Hand, whose 8 year old daughter was kidnapped by the terror group that day. Listen to the harrowing testimony of a father, one story, amongst thousands. Thank you for sharing your experience Thomas. This video is not for the feint of heart.

In this explosive interview, Amichai Chikli Minister of Diaspora Affairs of Israel delivers a powerful warning about the rise of radical Islam and the Muslim Brotherhood’s dangerous global ambitions, from establishing a Caliphate to imposing Sharia law across Europe and beyond. He slams the UK’s Labour government under Keir Starmer for its "fear-driven" approach to extremism, drawing chilling parallels to appeasement tactics before WWII. Discover why he believes Britain must act decisively to avoid a catastrophic wake-up call. Join the conversation on this critical fight for freedom and democracy!

A former paratrooper and reserve commander takes us from the frontlines to the world stage — describing life in Sderot, fighting inside Gaza (Machon Al-Quds, Nuseirat, Beit Hanoun) and the trauma of October 7. He explains how close Gaza is to Israeli towns, recalls the 2005 Gush Katif withdrawal, and shares raw, personal scenes from months spent in active combat — then returning home to face a different battle: the rise of antisemitism worldwide. What you’ll hear in this video: • A frontline commander’s personal testimony about October 7 and the months that followed. • Firsthand descriptions of operations in Gaza (Nuseirat, Beit Hanoun) and daily threats from tunnels and armed militants. • Reflections on the 2005 Gaza withdrawal (Gush Katif) and what it meant for local communities. • The psychological shift from military duty back to civilian life and confronting global antisemitism.

Tommy Robinson visits Re’im, the site of the Nova Festival massacre, during the two-year memorial of the October 7th atrocities. Hear the harrowing first-hand testimonies of survivors and witnesses as they recount what truly happened when Hamas terrorists attacked innocent festivalgoers. This is the raw, unfiltered truth of that dark day, as told by those who lived through it.

After watching previously unseen footage showing the massacre of 110 innocent people by Hamas on October 7th, Tommy Robinson shares his raw reaction and reflections. He speaks about what he witnessed, the mindset behind the attacks, and how the reality on the ground in Israel differs from what much of the media shows. This is not easy to watch — but it’s an honest account of what he saw and why he believes the world needs to understand the true nature of this conflict.

Today I visited the Kibbutz closest to the Gaza border. Where some 5,000 Hamas jihadist scum launched their attack on Israeli citizens on October 7th. I speak to this brave gentleman, Thomas Hand, whose 8 year old daughter was kidnapped by the terror group that day. Listen to the harrowing testimony of a father, one story, amongst thousands. Thank you for sharing your experience Thomas. This video is not for the feint of heart.

In this explosive interview, Amichai Chikli Minister of Diaspora Affairs of Israel delivers a powerful warning about the rise of radical Islam and the Muslim Brotherhood’s dangerous global ambitions, from establishing a Caliphate to imposing Sharia law across Europe and beyond. He slams the UK’s Labour government under Keir Starmer for its "fear-driven" approach to extremism, drawing chilling parallels to appeasement tactics before WWII. Discover why he believes Britain must act decisively to avoid a catastrophic wake-up call. Join the conversation on this critical fight for freedom and democracy!

A former paratrooper and reserve commander takes us from the frontlines to the world stage — describing life in Sderot, fighting inside Gaza (Machon Al-Quds, Nuseirat, Beit Hanoun) and the trauma of October 7. He explains how close Gaza is to Israeli towns, recalls the 2005 Gush Katif withdrawal, and shares raw, personal scenes from months spent in active combat — then returning home to face a different battle: the rise of antisemitism worldwide. What you’ll hear in this video: • A frontline commander’s personal testimony about October 7 and the months that followed. • Firsthand descriptions of operations in Gaza (Nuseirat, Beit Hanoun) and daily threats from tunnels and armed militants. • Reflections on the 2005 Gaza withdrawal (Gush Katif) and what it meant for local communities. • The psychological shift from military duty back to civilian life and confronting global antisemitism.

Tommy Robinson visits Re’im, the site of the Nova Festival massacre, during the two-year memorial of the October 7th atrocities. Hear the harrowing first-hand testimonies of survivors and witnesses as they recount what truly happened when Hamas terrorists attacked innocent festivalgoers. This is the raw, unfiltered truth of that dark day, as told by those who lived through it.

After watching previously unseen footage showing the massacre of 110 innocent people by Hamas on October 7th, Tommy Robinson shares his raw reaction and reflections. He speaks about what he witnessed, the mindset behind the attacks, and how the reality on the ground in Israel differs from what much of the media shows. This is not easy to watch — but it’s an honest account of what he saw and why he believes the world needs to understand the true nature of this conflict.

Today I visited the Kibbutz closest to the Gaza border. Where some 5,000 Hamas jihadist scum launched their attack on Israeli citizens on October 7th. I speak to this brave gentleman, Thomas Hand, whose 8 year old daughter was kidnapped by the terror group that day. Listen to the harrowing testimony of a father, one story, amongst thousands. Thank you for sharing your experience Thomas. This video is not for the feint of heart.

In this explosive interview, Amichai Chikli Minister of Diaspora Affairs of Israel delivers a powerful warning about the rise of radical Islam and the Muslim Brotherhood’s dangerous global ambitions, from establishing a Caliphate to imposing Sharia law across Europe and beyond. He slams the UK’s Labour government under Keir Starmer for its "fear-driven" approach to extremism, drawing chilling parallels to appeasement tactics before WWII. Discover why he believes Britain must act decisively to avoid a catastrophic wake-up call. Join the conversation on this critical fight for freedom and democracy!

A former paratrooper and reserve commander takes us from the frontlines to the world stage — describing life in Sderot, fighting inside Gaza (Machon Al-Quds, Nuseirat, Beit Hanoun) and the trauma of October 7. He explains how close Gaza is to Israeli towns, recalls the 2005 Gush Katif withdrawal, and shares raw, personal scenes from months spent in active combat — then returning home to face a different battle: the rise of antisemitism worldwide. What you’ll hear in this video: • A frontline commander’s personal testimony about October 7 and the months that followed. • Firsthand descriptions of operations in Gaza (Nuseirat, Beit Hanoun) and daily threats from tunnels and armed militants. • Reflections on the 2005 Gaza withdrawal (Gush Katif) and what it meant for local communities. • The psychological shift from military duty back to civilian life and confronting global antisemitism.

Tommy Robinson visits Re’im, the site of the Nova Festival massacre, during the two-year memorial of the October 7th atrocities. Hear the harrowing first-hand testimonies of survivors and witnesses as they recount what truly happened when Hamas terrorists attacked innocent festivalgoers. This is the raw, unfiltered truth of that dark day, as told by those who lived through it.

After watching previously unseen footage showing the massacre of 110 innocent people by Hamas on October 7th, Tommy Robinson shares his raw reaction and reflections. He speaks about what he witnessed, the mindset behind the attacks, and how the reality on the ground in Israel differs from what much of the media shows. This is not easy to watch — but it’s an honest account of what he saw and why he believes the world needs to understand the true nature of this conflict.

Today I visited the Kibbutz closest to the Gaza border. Where some 5,000 Hamas jihadist scum launched their attack on Israeli citizens on October 7th. I speak to this brave gentleman, Thomas Hand, whose 8 year old daughter was kidnapped by the terror group that day. Listen to the harrowing testimony of a father, one story, amongst thousands. Thank you for sharing your experience Thomas. This video is not for the feint of heart.

In this explosive interview, Amichai Chikli Minister of Diaspora Affairs of Israel delivers a powerful warning about the rise of radical Islam and the Muslim Brotherhood’s dangerous global ambitions, from establishing a Caliphate to imposing Sharia law across Europe and beyond. He slams the UK’s Labour government under Keir Starmer for its "fear-driven" approach to extremism, drawing chilling parallels to appeasement tactics before WWII. Discover why he believes Britain must act decisively to avoid a catastrophic wake-up call. Join the conversation on this critical fight for freedom and democracy!

A former paratrooper and reserve commander takes us from the frontlines to the world stage — describing life in Sderot, fighting inside Gaza (Machon Al-Quds, Nuseirat, Beit Hanoun) and the trauma of October 7. He explains how close Gaza is to Israeli towns, recalls the 2005 Gush Katif withdrawal, and shares raw, personal scenes from months spent in active combat — then returning home to face a different battle: the rise of antisemitism worldwide. What you’ll hear in this video: • A frontline commander’s personal testimony about October 7 and the months that followed. • Firsthand descriptions of operations in Gaza (Nuseirat, Beit Hanoun) and daily threats from tunnels and armed militants. • Reflections on the 2005 Gaza withdrawal (Gush Katif) and what it meant for local communities. • The psychological shift from military duty back to civilian life and confronting global antisemitism.

Tommy Robinson visits Re’im, the site of the Nova Festival massacre, during the two-year memorial of the October 7th atrocities. Hear the harrowing first-hand testimonies of survivors and witnesses as they recount what truly happened when Hamas terrorists attacked innocent festivalgoers. This is the raw, unfiltered truth of that dark day, as told by those who lived through it.

After watching previously unseen footage showing the massacre of 110 innocent people by Hamas on October 7th, Tommy Robinson shares his raw reaction and reflections. He speaks about what he witnessed, the mindset behind the attacks, and how the reality on the ground in Israel differs from what much of the media shows. This is not easy to watch — but it’s an honest account of what he saw and why he believes the world needs to understand the true nature of this conflict.

Today I visited the Kibbutz closest to the Gaza border. Where some 5,000 Hamas jihadist scum launched their attack on Israeli citizens on October 7th. I speak to this brave gentleman, Thomas Hand, whose 8 year old daughter was kidnapped by the terror group that day. Listen to the harrowing testimony of a father, one story, amongst thousands. Thank you for sharing your experience Thomas. This video is not for the feint of heart.

In this explosive interview, Amichai Chikli Minister of Diaspora Affairs of Israel delivers a powerful warning about the rise of radical Islam and the Muslim Brotherhood’s dangerous global ambitions, from establishing a Caliphate to imposing Sharia law across Europe and beyond. He slams the UK’s Labour government under Keir Starmer for its "fear-driven" approach to extremism, drawing chilling parallels to appeasement tactics before WWII. Discover why he believes Britain must act decisively to avoid a catastrophic wake-up call. Join the conversation on this critical fight for freedom and democracy!

A former paratrooper and reserve commander takes us from the frontlines to the world stage — describing life in Sderot, fighting inside Gaza (Machon Al-Quds, Nuseirat, Beit Hanoun) and the trauma of October 7. He explains how close Gaza is to Israeli towns, recalls the 2005 Gush Katif withdrawal, and shares raw, personal scenes from months spent in active combat — then returning home to face a different battle: the rise of antisemitism worldwide. What you’ll hear in this video: • A frontline commander’s personal testimony about October 7 and the months that followed. • Firsthand descriptions of operations in Gaza (Nuseirat, Beit Hanoun) and daily threats from tunnels and armed militants. • Reflections on the 2005 Gaza withdrawal (Gush Katif) and what it meant for local communities. • The psychological shift from military duty back to civilian life and confronting global antisemitism.

Tommy Robinson visits Re’im, the site of the Nova Festival massacre, during the two-year memorial of the October 7th atrocities. Hear the harrowing first-hand testimonies of survivors and witnesses as they recount what truly happened when Hamas terrorists attacked innocent festivalgoers. This is the raw, unfiltered truth of that dark day, as told by those who lived through it.

After watching previously unseen footage showing the massacre of 110 innocent people by Hamas on October 7th, Tommy Robinson shares his raw reaction and reflections. He speaks about what he witnessed, the mindset behind the attacks, and how the reality on the ground in Israel differs from what much of the media shows. This is not easy to watch — but it’s an honest account of what he saw and why he believes the world needs to understand the true nature of this conflict.

Today I visited the Kibbutz closest to the Gaza border. Where some 5,000 Hamas jihadist scum launched their attack on Israeli citizens on October 7th. I speak to this brave gentleman, Thomas Hand, whose 8 year old daughter was kidnapped by the terror group that day. Listen to the harrowing testimony of a father, one story, amongst thousands. Thank you for sharing your experience Thomas. This video is not for the feint of heart.

In this explosive interview, Amichai Chikli Minister of Diaspora Affairs of Israel delivers a powerful warning about the rise of radical Islam and the Muslim Brotherhood’s dangerous global ambitions, from establishing a Caliphate to imposing Sharia law across Europe and beyond. He slams the UK’s Labour government under Keir Starmer for its "fear-driven" approach to extremism, drawing chilling parallels to appeasement tactics before WWII. Discover why he believes Britain must act decisively to avoid a catastrophic wake-up call. Join the conversation on this critical fight for freedom and democracy!

Contact Us

Contact Us

Writers, other artists who are interested in taking part, we are here for any request, question, or idea

About us

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Aliquam sodales orci nec quam fringilla, in viverra nisl viverra. Pellentesque quis erat dolor. In elementum egestas fringilla.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Aliquam sodales orci nec quam fringilla, in viverra nisl viverra. Pellentesque quis erat dolor. In elementum egestas fringilla.

All rights reserved to Israel Digital Center | Official Website 2025

All rights reserved to Israel Digital Center | Official Website 2025

ISRAEL DIGITAL CENTER

About us

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Aliquam sodales orci nec quam fringilla, in viverra nisl viverra. Pellentesque quis erat dolor. In elementum egestas fringilla.

All rights reserved to Israel Digital Center

| Official Website 2025